![]()

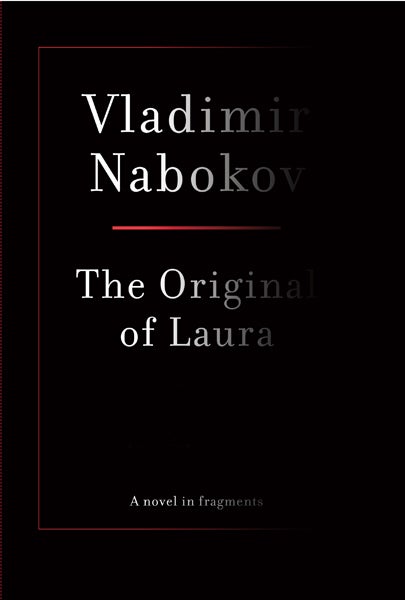

(The 138 index cards that comprise Vladimir Nabokov’s The Original of Laura. Source.)

Finally got around to reading this. There was no need to put it off, fearing its size, given that it only took me about an hour and a half to read (and I do not read fast). What does it tell you when a 275-page, 3-pound book can be read at a slowish pace in under two hours? For starters, that it’s far slighter than it has been made to look. Bloated is the word. Of course, Nabokov is not to blame, but his son, Dmitri, who in the intro exaggerates the book’s significance even as he derides the supposed legions of academic scavengers who eagerly drool over every last crumb of Nabokoviana. (A case of biting the hand that feeds you if ever there was one, but Dmitri clearly inherited his father’s unsavory snobbishness; the intro is an obnoxious exercise in score-settling and belittlement: apparently the only truly worthy human beings are the Nabokovs, pere, mere and fils.)

![]()

The book obviously cost a fortune to make, and is bound in cloth and printed on heavy card-stock. It certainly looks nice, and the cover hidden under the dust jacket is particularly clever. But it is transparently a ploy by son, agent and publisher to get people to fork over 35 bucks for material which would have been more fittingly presented in a literary journal, and would have taken up no more than 40 or 50 pages of such a publication. Instead we get 275 “pages,” half of them devoid of text, and the rest featuring an average of maybe 50 words of content, first in manuscript form (facsimiles of Nabokov’s famous notecards, a format fictionalized in Pale Fire), and then again in transcript. The whole thing is subtitled “A Novel in Fragments,” but it is in reality a fragment of a novel. “Unfinished masterpiece” is just disingenuous: try “barely-begun minor work” or, less generously, “various burps of senilia, some brilliantly ripe.”

(OK, that was gross.)

In any case, the manuscript’s slightness doesn’t make reading it a waste of time, and some of it is great fun. Several of the passages are quite exciting in their surreally wacky, slightly unhinged playfullness. Consider:

I hit upon the art of thinking away my body, my being, mind itself. To think away thought—luxurious suicide, delicious dissolution! Dissolution, in fact, is a marvelously apt term here, for as you sit relaxed in this comfortable chair (narrator striking its armrests) and start destroying yourself, the first thing you feel is a mounting melting from the feet upward…(243)

Speaking of armchairs, what do you know about fleshy fauteuils? Here is Philip Wild, the obese subject of the preceding reverie, now in flagranto with his much-younger wife, Flora:

The only way he could possess her was the most [ ] position of copulation: he reclining on cushions: she sitting in the fauteuil of his flesh with her back to him. The procedure—a few bounces over very small humps—meant nothing to her[.] She looked at the snowscape on the footboard of the bed—at the [curtains]; and he holding her in front of him like a child being given a sleighride down a short slope by a kind stranger, he saw her back, her hip[s] between his hands.

Like toads or tortoises neither saw each other’s faces. See animaux. (197-9 (yes, that’s a full three pages of text))

Here we are in that familiar territory of lechery and (quasi-)pedophilia. In this case funny, but icky, too. These dirty-old-man flights of fancy are outrageously comical, like a dream from one of Freud’s surprisingly in-your-face early case studies—in this case it’s literally balls-out, as Wild addresses one “Aurora Lee,” apparently a high-school sweetheart:

Your painted pout and cold gaze were…very like the official lips and eyes of Flora, my wayward wife, and your flimsy frock of black silk might have come from her recent wardrobe. You turned away, but could not escape, trapped as you were among the close-set columns of moonlight and I lifted the hem of your dress…and stroked, moulded, pinched ever so softly your pale prominent nates, while you stood perfectly still as if considering new possibilities of power and pleasure and interior decoration. At the height of your guarded ecstasy I thrust my cupped hand from behind between your consenting thighs and felt the sweat-stuck folds of a long scrotum and then, further in front, the droop of a short member. Speaking as an authority on dreams, I wish to add that this was no homosexual manifestation but a splendid example of terminal gynandrism….But quite apart from that, in a more disgusting and delicious sense, her little bottom, so smooth, so moonlit, a replica, in fact, of her twin brother’s charms, sampled rather brutally on my last night at boarding school, remained inset on the medal[l]ion of every following day. (202-7)

So I’ve shared the best of the naughty bits. But behind what may look like mere high-class erotica (which is somehow unseemlier and creepier than straight-up porn) there is a kind of free-wheeling, decadent absurdism at work here, a sex-weary, sex-hungry, sex-mocking comic spirit that is somewhat interesting. But I admit I’m already bored.

I’ve slipped into an awkward book-reviewy tone, but let me conclude this little field report by saying that the thing’s worth reading—if not worth buying. (It’s a “burn it,” as Kot and DeRogatis would say.) What’s most valuable here is the thrill of seeing an artist in process, the privilege of getting behind the veil, the better to recognize the hand in the work—the hand of a man, not a god.